A Cajun Craftsman Preserves the Hallowed Ping of History

By JON PARELES

Published: April 30, 2006

SCOTT, La., April 26 � The triangle may seem like a humble instrument: nothing more than a bent steel rod hit with a steel stick, merrily clanging away behind the fiddle and accordion of a traditional Cajun band. Visitors here in the bayou country of Acadiana often buy them as souvenirs at tourist stops.

Skip to next paragraph

Enlarge This Image

Ozier Muhammad/The New York Times

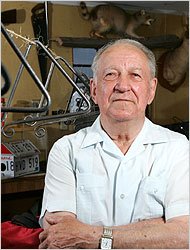

Dieu Donn� Montoucet, 80, makes

triangles used in Cajun music.

But there are triangles, and then there are the triangles made by Dieu Donn� Montoucet, an 80-year-old Cajun who goes by Don and whose hand-forged, antique-steel, virtually indestructible triangles are prized by musicians for the way they ring.

"They have a lot of volume, they have a lot of clarity and they have a lot of sustain," said Barry Ancelet, a professor of Francophone studies at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette who is a historian of Cajun music and a triangle player. "On a final note they'll continue ringing like a church bell."

The simple triangle paces traditional Cajun music, and its peal echoes beyond the bayou. While Cajun music's stronghold is around Lafayette, about 130 miles west of New Orleans, its two-step beat and high, tense vocal style have made their way into American music like country and New Orleans rhythm and blues.

Cajun music is a staple of the annual New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. [The 37th edition started on Friday and runs through next Sunday.] Advance ticket sales alone have topped 100,000. Among its headliners are Bruce Springsteen, Paul Simon and Dave Matthews. But the lineup also includes hundreds of Louisiana bands, among them traditionalist Cajun bands like Steve Riley and the Mamou Playboys, who use Mr. Montoucet's triangles.

Hurricane Katrina did not reach Acadiana, and Cajun music may be making new inroads in the 21st century, since many New Orleans residents � musicians included � evacuated west into Cajun country.

A small printed sign on Mr. Montoucet's workshop reads, "Don Montoucet, Lafayette � Lafayette Parish, Triangles � Cajun." His workbench and his office occupy one corner of his son-in-law's furniture warehouse. Inside, a dozen triangles hang on the wall; there's also a deer head, a stuffed raccoon and some birdhouses made from old license plates. A larger sign announces that Mr. Montoucet does Louisiana state vehicle inspections, his day job.

Mr. Montoucet has never had just one job. He drove a school bus for 45 years and began fixing cars at his own Don's Garage in 1940. From 1968 to 1996 he played accordion in his own Cajun band, Don Montoucet and the Wandering Aces. It changed its name to Don Montoucet and the Mulate Playboys when it became the house band at the well-known Mulate's restaurants in Breaux Bridge, Baton Rouge and New Orleans.

There's history in Mr. Montoucet's triangles. It's an old instrument; Mr. Ancelet says that triangles are described in accounts of medieval and Renaissance music. His triangles have a distinctive tight, flat loop at each end. He copied the design from a set � triangle and beater � that he inherited from his grandfather, a blacksmith who came to Louisiana from France. He made his first set around 40 years ago for a friend who knew he did ironwork.

Soon word got around, not just to Acadiana but to Canada and beyond. He sells the triangles himself in his workshop; they are also sold at the Savoy Music Center in Eunice, La., a stronghold of Acadian traditional music founded in 1960 by the musician and accordion builder Marc Savoy. They cost $35.

Mr. Montoucet makes the triangles from the U-shaped tines of salvaged old hayrakes: huge wheeled contraptions pulled by horses or tractors. The tines are springy and patinaed with rust from sitting in wet fields. He does not shine them up. "They can't be too rusty," he said. "The first thing that people ask me is, 'Is that the old iron?' They don't want to hear nothing else."

With an acetylene torch � he used to use a coal furnace � Mr. Montoucet heats the tines to straighten them, then cuts them to the right length. (One tine makes a triangle and its beater.) He heats them again to bend them into shape and keeps them red-hot to make the loops at the end. "It takes 250 licks of that big forge hammer to make one," he said.

The key to the sound, he says, is in the final stage: the tempering that heats and cools the steel for strength. He said: "If you heat them too hot, or not enough, it makes a difference. I can show you how to temper them, but if you don't have it here ..." He pointed to his head.

The hayrakes were collected through the years by a friend who works as a trucker. There is no new supply. "The iron is getting scarce," Mr. Montoucet said. "A lot of these farmers, they were glad to get rid of these hayrakes and glad to get them out of the way. But they got no more, pardner. I have a few of them left. My oldest son says, 'Dad, what you going to do when you can't get any more steel?' I say, 'Don't you think it's time for me to retire?' "

The triangles are guaranteed for life against the walloping a Cajun musician will give them. In the days before amplification, the triangle might have been the only thing heard by dancers at the far edges of a party. Mr. Montoucet knows of only one of his triangles that has broken: one that he made for Christine Balfa, the daughter of the great Cajun fiddler Dewey Balfa. After a forensic examination of the pieces, Mr. Montoucet found that there had been a hairline crack in the original hayrake tine.

Although Mr. Montoucet makes triangles in set sizes � usually from 8 to 12 inches on a side � they are anything but standardized. Mr. Montoucet played a few of his 9-inch triangles: each had a different note and a different ring.

"One day a lady came in and said: 'How come they're all different sounds? Why can't you make them all the same sound?' We were five or six men here, and I said, 'Lady, it's like this: if all us men liked the same woman, it wouldn't work.' Everybody likes different things. Some people like gumbo, some people don't like gumbo, but I don't know too many people who don't like gumbo."

Cajun musicians do not simply hit the triangle. A Cajun two-step or waltz is defined by a quick-changing ping and clank that vary depending on how the triangle is gripped: with a few fingers, an open palm, a closed fist. Mr. Montoucet smiled as a visitor attempted to coordinate the rhythmic tapping, clasping and unclasping.

"You ought to see my little 18-month-old great-grandchild doing that," he said. "He comes, and he gets all my tools, and then he picks up the triangle. His father says, 'He's probably going to be a mechanic.' And I say, 'He might be a musician too.' "

No comments:

Post a Comment